JEDI: Justice, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion

Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.

James Baldwin

Hello, Padawans! And welcome to my thoughts on our JEDI journey. While JEDI is a super cool acronym, nothing about this journey will have anything to do with Star Wars. Really, the goal is more like getting to Star Trek’s queer space utopia (or the one that would have existed had Berman not interfered) while skipping the Bell Riots entirely. And that’s going to take a lot of work.

Our society, and therefore our jobs and institutions, are set up to default to cisgender- heterosexual- white– abled- and Christian-normativity. We all internalize this normativity, because we’re raised in them. Which means, we all have to work really hard to unlearn or decolonize.

Not doing this work can lead to a micro-aggressive or even hostile spaces (especially workplaces, since people can’t just leave them if they’re not a good environment) for those from marginalized communities. The good news is that if we make the time and effort to do so, we can set up our workplaces and other spaces to be inclusive, focus on equity first, and work toward cultural competencies that value and retain employees and supporters from marginalized communities.

Before I get into the nitty gritty, I want to establish a base-point to work from. I think that Dafina-Lazarus Stewart has a great explanation of JEDI principles:

Diversity asks, “who is in the room?” Equity responds, “Who is trying to get in the room but can’t? Whose presence in the room is under constant threat of erasure?”

Inclusion asks, “Have everyone’s ideas been heard?” Justice responds, “Whose ideas won’t be taken as seriously because they aren’t in the majority?”

Diversity asks, “How many more of [pick any minoritized identity] group do we have this year than last?” Equity responds, “What conditions have we created that maintain certain groups as the perpetual minority here?”

Inclusion asks, “Is the environment safe for everyone to feel like they belong?” Justice challenges, “Whose safety is being sacrificed and minimized to allow others to be comfortable maintaining dehumanizing views?”

Fragility Poisons Justice

I want to emphasize inclusion and justice in this description. Too often, organizations or groups decide they want diversity, and they recognize they need to work on equity to attract more diverse talents. But, they don’t do anything about their company culture to ensure that they can retain the talent they get (inclusion), and they forget the justice portion entirely, assuming that they can make new square pegs fit in round holes. They keep the cisgender- heterosexual- white- abled- and Christian-normativity, and expect marginalized people to squeeze themselves to fit that culture or leave their true selves outside.

I have a hard time accepting diversity as a synonym for justice. Diversity is a corporate strategy. It’s a strategy designed to ensure that the institution functions in the same way that it functioned before, except now you have some black faces and brown faces. It’s a difference that doesn’t make a difference.

Diversity without structural transformation simply brings those who were previously excluded into a system as racist, as misogynistic, as it was before.

Angela Davis

The biggest way that organizations do this is through fragility. Instead of appreciating and celebrating the marginalized people working to better an organization or group, some people and organizations tend to shoot the messenger and expose them to fragility.

Fragility is pretty much what it sounds like – being easily breakable, forcing others to be extremely delicate or tip toe around your feelings. While it’s okay for teacups, it is horrible for people with relative privilege to subject those from marginalized communities to.

Let’s take a look at white fragility for a second to better understand it. White fragility is a series of defensive moves that white people use to derail a conversation about race when they become challenged or uncomfortable, and particularly when they feel they might be considered a bad actor.

If you’ve been in a conversation about race, you’ve likely seen it. It might look like tone policing; paragraphs of historical details about their lives that end with a conclusion that they “couldn’t be a racist” because x, y, and z; statements that they are color-blind; “Not All” statements; “All Lives” statements; claims that it doesn’t matter if you are “white, black, green, or purple” (usually in that order, somehow); their proximity and relationships to people of color; tokenizing other marginalized people and using them as a beard; dismissal of the critique due to a personality flaw they’ve decided the marginalized person bringing it up has; and usually ends with claims of their allyship or in weaponized white tears.

White fragility holds racism in place by making it near impossible for people of color to engage people who use it in meaningful conversations about race. There’s always a way in which the person of color will have “not done it correctly” and that goalpost will move in any direction necessary to prevent the conversation from taking place.

I actually had the weirdest experience with white fragility a week before writing this up where a white progressive used JEDI training buzzwords as a weapon against me. It was odd and very dehumanizing being talked down to with words that are meant to help me get an equal footing, but was being used to chastise me into silence (and then chastise me when silence was achieved).

People from marginalized identities don’t enjoy bringing these topics up. If they’ve been burned as many times as I have, they might be afraid of repercussions or being labeled as “disruptive” or “not fitting in with company culture” (both are things that will get notes in your employee file and sometimes will end in your lay off) but they want to advance the organization or end their struggles within it. On top of that constantly having to explain racism or why something is racist has a cumulative impact on marginalized peoples’ social, mental, and emotional health.

Part of inclusion and justice work is being sure that you are listening to people when they bring problems forward, trusting their leadership and expertise in their own experience, and valuing their safety and humanization over others comfort, yours included.

So, how do you avoid weaponizing fragility when someone tells you of a problem they are facing? It’s natural to have a guttural reaction. No one wants to be part of the problem, especially when they think they’ve done a lot of work on the problem themselves. But it’s very important to sit in that discomfort and not expose the person telling you of their marginalization to it.

There’s one fragility idea that’s so ingrained in our society that it makes it nearly impossible to have conversations about racism or homophobia or transphobia etc. And that is the idea that racism, homophobia, ableism etc is a conscious action conducted by bad people. But that idea causes a dichotomy that isn’t true and helps people who aren’t “bad people” distance themselves from responsibility to take a look at the harm of their actions.

It’s important to note that we are ALL racist (at least a little bit) and ALL homophobic (at least a little bit) and ALL ableist (at least a little bit), because we’ve been socialized to be so (part of the reason we don’t see it is because we’ve also been socialized to believe that only the most heinous acts qualify as racism, homophobia, or transphobia). You weren’t exempt from life-long conditioning to be so, and neither was I – that’s why we are on this life-long JEDI journey. When you realize that, it makes it easier – I hope – to do the work and stay on the path instead of spending your energy distancing yourself from the accusation and continuing to perpetuate the problem.

Resist the urge to defend yourself and claim you aren’t doing it; work on mitigating harm.

I’m a big proponent of “know better, do better” method (popularized by Maya Angelou). There’s always things that we don’t know about because we don’t experience them. We read what we read and parrot what we hear, and can sometimes unwittingly repeat something that is micro-aggressive or coded language (dog whistles) meant to do harm to a community – especially in the case of transgender issues where the most transphobic people are getting the most air time and we rarely get to hear from transgender people (except the problematic ones).

We have to be willing to listen to feedback from people from marginalized communities. And sometimes we have to ask questions to learn better, know better, and then do better. It’s important to feel safe to do that, which means, in spaces where marginalized people are giving you permission to ask them (This is important! Remember a few paragraphs ago when I said that explaining racism has cumulative impacts? Be sure that you have permission to ask and be prepared to be told “not right now.” Google exists too.), you should feel free to use the words you have rather than being afraid to use any. Be prepared and open to learn the words that are more affirming to their communities and be prepared and willing to accept whatever tone you learn that in. Some dog whistles against certain communities are egregious and painful to hear and you might encounter a feeling or two if you say them. But it’s important to the learning process to use the words you have.

A great way to learn about identities you don’t share is to follow people from that identity on Twitter. We have social media and mostly we use it for silliness, but it’s also a great equalizing tool, helping us hear voices that until now have been drowned out and silenced by the majority culture. Follow people from identities and learn about things that impact them. Follow groups that discuss identity issues. Listen (read) and learn.

Other tips and tricks: listen to what the person is saying and try to empathize with the experience; don’t center yourself or your feelings in the conversation; educate yourself rather than leaning on that person for an education (ask rather than demand help if you aren’t sure where to start looking); think about your responses and if they uphold or dismantle the -ism you’re working with; and never, ever expect or demand someone from a marginalized community to center you or your feelings in a conversation about things that harm them.

If you are from a privileged community and observe fragility or see someone is being targeted by someone who is weaponizing fragility to silence them, either by tone policing, gaslighting, or using other manipulative tactics, use your place of relative privilege to support and amplify them. Remind the person that these are uncomfortable, but necessary conversations, and that people who experience marginalization should be believed and listened to regarding their own experiences.

Remind them that the marginalized person’s emotions are valid, they don’t get to dictate the terms of a conversation, and they don’t get to dictate the ways that people talk about harm being done to them. By derailing the discussion, they will never solve the problem.

While silence may feel like a neutral stance in an argument between two people (thanks normative upbringing!) it is actually siding with the person doing harm since the harm will continue and the marginalized person receives the message that they are alone.

Be an Accomplice, Not an Ally

Half the time someone harms me or exhibits fragility, they tell me they’re an ally in the same breath. It’s become this buzzword that everyone knows they’re supposed to “be” but not many know (or seem to care) how to be one.

Apparently, and I just learned this, ally comes from the Latin word alligare, meaning “to bind to” so it should be a powerful word with a powerful action. But the term “ally” has been so overused, it’s pretty much meaningless.

Story time: a Christian person I know was lamenting the fact that LGBTIQA2+ people sometimes didn’t immediately trust that she was an ally; because of her faith, they were wary of her. She went so far as to compare them questioning her allyship to the discrimination that LGBTIQA2+ people face every day which…is not something an ally would do, but okay.

I asked what sort of allyship she had done. Had she worn a button to indicate she was a safe person? Did she stand up for LGBTIQA2+ people when they were being verbally or physically attacked by other Christians? Had she chosen an affirming church? Had she talked to her church about the importance of affirmation of LGBTIQA2+ identities? Her answer was that she “supported” queer people. Not in any meaningful, actualized way, but in theory, by not being a homophobic ass.

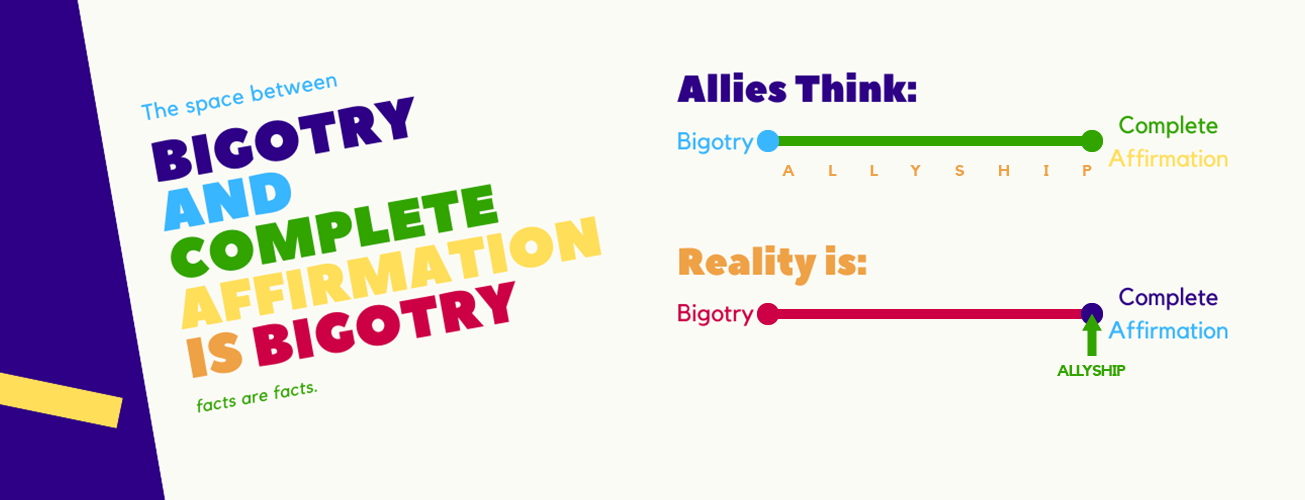

That shouldn’t be how low the bar is for a word like “ally” if it means “to bind to.” But it is. People have come to think of anyone who isn’t actively being a bigot as being an ally. People want to fill in all the space between bigotry and complete affirmation as ally-space when really the only space for allies is on the far end where complete affirmation is. Everything other than complete affirmation is just bigotry.

Story time: In the early 2000’s when states were trying to pass Constitutional Amendments to prevent same sex marriage, I was doing database entry for a nonprofit that canvassed my tiny bigoted town. I learned how a lot of people were planning to vote in that election and why. People who claimed to be allies in classrooms and community groups were voting to prevent marriage equality. But they genuinely considered themselves as having earned the right to call themselves an ally, somehow. So we need a better word.

What people from marginalized communities need are accomplices. An accomplice is someone who does something active with you. It’s a fierce title that indicates meaningful, actual help in the struggle against systems of oppression. It indicates a willingness to assist and participate in what is unlawful in order to do what is right.

Throughout history, many parts of me were illegal. My mixed-raced heritage was against the law. My sexual orientation was against the law. In some states, me using a public restroom is against the law. There was a saying in the queer community long ago, “Be gay, do crimes.” It was a nod to the fact that our very existence was illegal, so why not do the crimes we needed to survive, which were also illegal. Nowadays, you’ll often hear the variation “Be they, do crimes.” since many laws and handbooks and whatnot don’t account for anyone living beyond a “he or she” binary gender construct.

Being alive and living well for some people living within marginalized identities requires crime. By being our accomplices and actively helping us navigate and resist a system that harms us, you are showing those your life touches that you recognize the institutions as the oppressive structures they are and you show us that you are willing to work with us to help dismantle it.

Part of being an accomplice is realizing that from where you stand, from a point of relative privilege, you have less to lose and more energy and footing to make change. In the case of that Christian, it could be sitting down with her church and making sure they understood affirmation – not by trying to explain it herself, since she clearly doesn’t have the knowledge to do that work, but by either amplifying someone else who understands and lives that experience or by providing resources to her church and ensuring they followed through.

And that’s much more valuable than claiming to be an ally as a title when someone questions your intentions.

Actions for Individuals in the Environmental Movement

There’s this article in Outside Magazine that I think shows what it’s like to be a member of the LGBTIQA2+ community in the environmental movement. The article is called “How Being LGBTQ Affected my Appalachian Trail Thru-Hike” by Lucy Parks. Lucy illustrates what visibly queer people and especially trans nonbinary people go through while enjoying our public lands and within our environmental organizations – as well as in the larger society that leans cisgender- and heterosexual-normative.

They talk about the visible discomfort of others and the struggle others have guessing our genders from our presentation – because it’s commonly accepted as polite to guess and address people based on our guesses. It made hiking the Appalachian Trail incredibly lonely for them. A lot of times, queer and especially trans people in our organizations are lonely because they don’t get to feel the social affirmation that others feel by being cisgender – the normalized identity.

And there are different levels of this – shock, terror, uneasiness, and sometimes even hostility – that are lobbed at trans and nonbinary people when people are confused about “what” we are.

Sometimes when people accept who we say we are on a surface level, they indicate that they don’t believe us by the way in which they treat us. For example: when people invite “women and nonbinary people” to an event and address the group as “Ladies,” what they are signaling is that they are only prepared to see AFAB (assigned female at birth) nonbinary people and they consider those people Women Lite.

One of the easiest ways to affirm LGBTIQA2+ people is not to give into the social training that says it’s polite to assume gender based on an interpretation of someone’s presentation. And a second way is to pay attention to and use affirming pronouns, honorifics, and names.

Pronouns are as important as names when it comes to affirming trans and nonbinary people, and yet sometimes people argue or give lectures when informed of someone’s pronoun.

Pronouns are one of the ways in which we think of ourselves and portray our identities. When someone asks you to use their pronouns or corrects you when you use the wrong ones, they are asking you and trusting you to respect their identity. When people use the wrong pronouns, that can lead to a person feeling disrespected, and could exacerbate any gender dysphoria or feelings of exclusion or alienation they feel. Purposefully ignoring or disrespecting someone’s pronouns is an act of oppression and verbal violence.

If you don’t know someone’s pronoun, you can introduce yourself with your own pronouns so that they know you’re a safe person to tell.

If you make a mistake after you know, it’s important not to make a big deal about it (so that the harmed party feels like they have to make you feel better or so that it draws more attention to the person being harmed). Apologize quickly or thank them for reminding you, repeat the correct pronoun, and move on. “Thank you for reminding me, they will contact you.”

If you hear someone else misgender someone while they are not in the room, and you know they are out in this space and have permission to correct (This is important! Know that they are out in that space and not “stealthing” with non-affirming pronouns for safety reasons), correct them politely without making a big deal: “Chris uses they pronouns.”

Something that helps immensely is practice. Instead of automatically gendering people you don’t know, start remembering that gender isn’t a visible thing. Practice referring to people you don’t know in a non-gendered way. And practice people’s pronouns when they change. It took however many decades you’ve been alive to learn to do it the way you’re doing, it’ll take some practice to change.

When my friends change their name and/or pronouns, I repeat the change to myself (after congratulating them!). So, I might get off the phone and say “Chris is they. Chris is they. Chris is they” while picturing my friend in my mind. It does help.

It’s also important to realize that there are any number of neo-pronouns and you might have to learn new words. When I first came out as trans in 2001, I tried to get people to use ze/zem for me, but no one would do it, and most people outside of my tight knit LGBTIQA2+ community laughed at me or rolled their eyes when I brought it up. I went back to being misgendered for 17 years before insisting people start using they/them.

Don’t be a person someone has to be misgendered for 17 years for. Learn the new words, please.